Coding with Practica

Now that you have Practice installed (if not, do this first), it's time to code a great app using it and understand its unique power. This journey will inspire you with good patterns and practices. All the concepts in this guide are not our unique ideas, quite the opposite, they are all standard patterns or libraries that we just put together. In this tutorial we will implement a simple feature using Practica, ready?

Pre-requisites

Just before you start coding, ensure you have Docker and nvm (a utility that installs Node.js) installed. Both are common development tooling that are considered as a 'good practice'.

What's inside that box?

You now have a folder with Practica code. What will you find inside this box? Practica created for you an example Node.js solution with a single component (API, Microservice) that is called 'order-service'. Of course you'll change its name to something that represents your solution. Inside, it packs a lot of thoughtful and standard optimizations that will save you countless hours doing what others have done before.

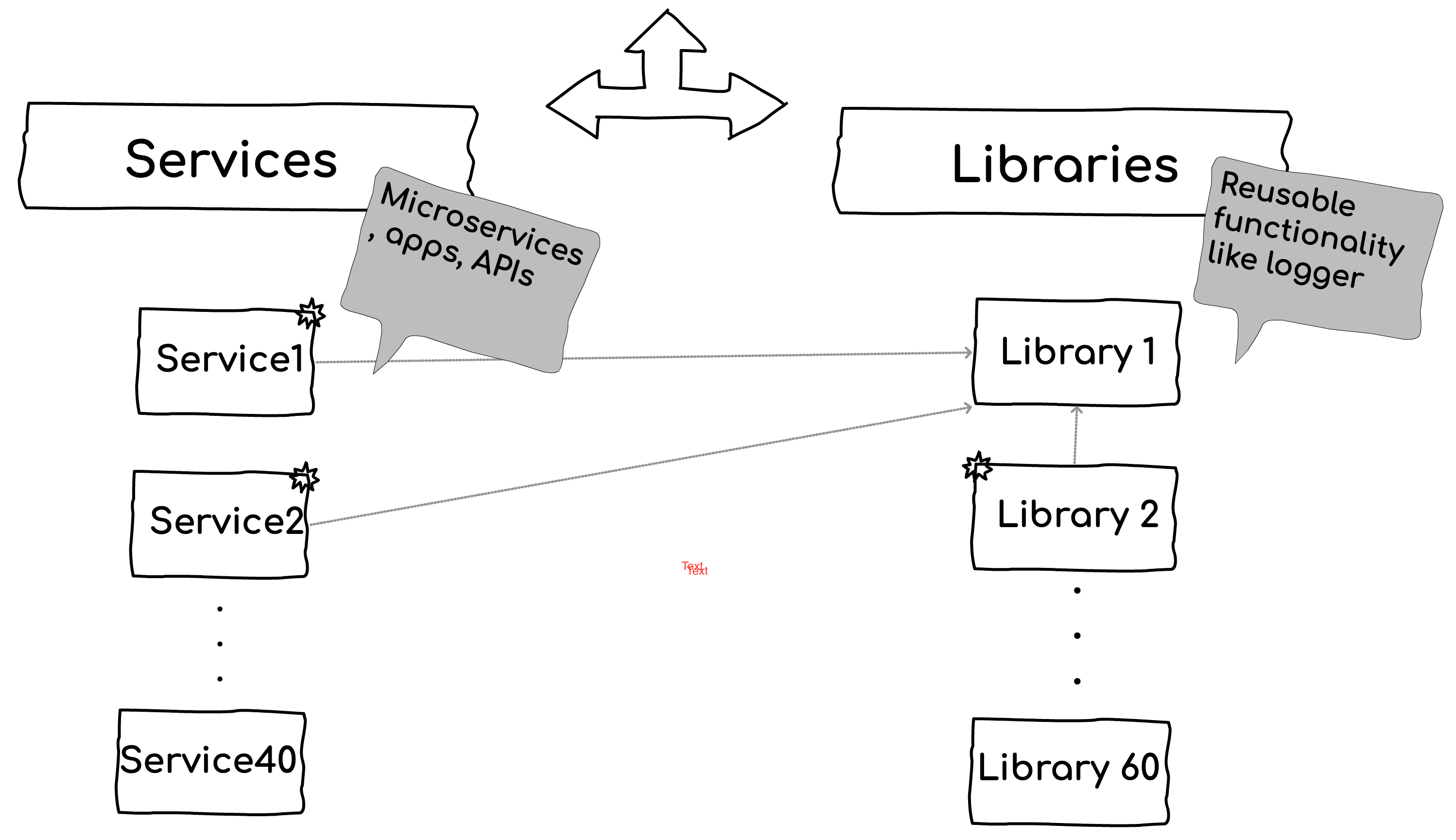

Besides this component, there are also a bunch of reusable libraries like logger, error-handler and more. All sit together under a single root folder in a single Git repository - this popular structure is called a 'Monorepo'.

A typical Monorepo structure

A typical Monorepo structure

The code inside is coded with Node.js, TypeScript, express and Postgresql. Later version of Practica.js will support more frameworks.

Running and testing the solution

A minute before we start coding, let's ensure the solution starts and the tests pass. This will give us confidence to add more and more code knowing that we have a valid checkpoint (and tests to watch our back).

Just run the following standard commands:

- CD into the solution folder

cd {your-solution-folder}

- Install the right Node.js version

nvm use

- Install dependencies

npm install

- Run the tests

npm test

Tests pass? Great! 🥳✅

They fail? oppss, this does not happen too often. Please approach our discord or open an issue in Github? We will try to assist shortly

- Optional: Start the app and check with Postman

Some rely on testing only, others like also to invoke routes using POSTMAN and test manually. We're good with both approach and recommend down the road to rely more and more on testing. Practica includes testing templates that are easy to write

Start the process first by navigating to the example component (order-service):

cd services/order-service

Start the DB using Docker and install tables (migration):

docker-compose -f ./test/docker-compose.yml up

npm run db:migrate

This step is not necessary for running tests as it will happen automatically

Then start the app:

npm start

Now visit our online POSTMAN collection, explore the routes, invoke and make yourself familiar with the app

Note: The API routes authorize requests, a valid token must be provided. You may generate one yourself (see here how), or just use the default development token that we generated for you 👇. Put it inside an 'Authorization' header:

Bearer eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJleHAiOjE3MzM4NTIyMTk5NzEsImRhdGEiOnsidXNlciI6ImpvZSIsInJvbGVzIjoiYWRtaW4ifSwiaWF0IjoxNzEyMjUyMjE5fQ.kUS7AnwtGum40biJYt0oyOH_le1KfVD2EOrs-ozclY0

We have the ground ready 🐥. Let's code now, just remember to run the tests (or POSTMAN) once in a while to ensure nothing breaks

The 3 layers of a component

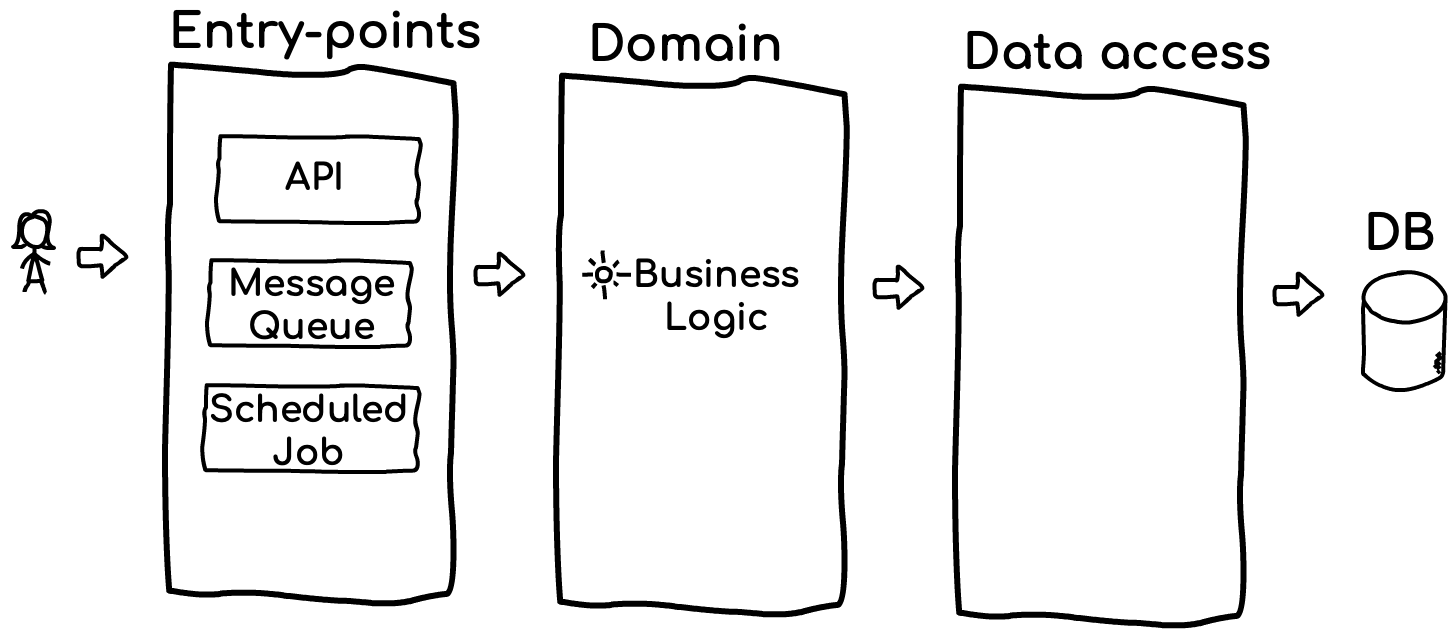

A typical component (e.g., Microservice) contains 3 main layers. This is a known and powerful pattern that is called "3-Tiers". It's an architectural structure that strikes a great balance between simplicity and robustness. Unlike other fancy architectures (e.g. hexagonal architecture, etc), this style is more likely to keep things simple and organized. The three layers represent the physical flow of a request with no abstractions:

A typical Monorepo structure

A typical Monorepo structure

- Layer 1: Entry points - This is the door to the application where flows start and requests come-in. Our example component has a REST API (i.e., API controllers), this is one kind of an entry-point. There might be other entry-points like a scheduled job, CLI, message queue and more. Whatever entry-point you're dealing with, the responsibility of this layer is minimal - receive requests, perform authentication, pass the request to be handled by the internal code and handle errors. For example, a controller gets an API request then it does nothing more than authenticating the user, extract the payload and call a domain layer function 👇

- Domain - A folder containing the heart of the app where the flows, logic and data-structure are defined. Its functions can serve any type of entry-points - whether it's being called from API or message queue, the domain layer is agnostic to the source of the caller. Code here may call other services via HTTP/queue. It's likely also to fetch from and save information in a DB, for this it will call the data-access layer 👇

- Data-access - Your entire DB interaction functionality and configuration is kept in this folder. For now, Practica.js uses ORM to interact with the DB - we're still debating on this decision

Now that you understand the structure of the example component, it's much easier to code over it 👇

Let's code a flow from API to DB and in return

We're about to implement a simple feature to make you familiar with the major code areas. After reading/coding this section, you should be able to add routes, logic and DB objects to your system easily. The example app deals with an imaginary e-commerce app. It has functionality for adding and querying for Orders. Goes without words that you'll change this to the entities and columns that represent your app.

🗝 Key insight: Practica has no hidden abstractions, you have to become familiar with the (popular) chosen libraries. This minimizes future scenarios where you get stuck when an abstraction is not suitable to your need or you don't understand how things work.

Requirements - - Our missions is to code the following: Allow updating an order through the API. Orders should also have a new field: Status. When trying to edit an existing order, if the field order.'paymentTermsInDays' is 0 (i.e., the payment due date is now) or the order.status is 'delivered' - no changes are allowed and the code should return HTTP status 400 (bad request). Otherwise, we should update the DB with new order information

1. Change the example component/service name

Obviously your solution, has a different context and name. You probably want to rename the example service name from 'order-service' to {your-component-name}. Change both the folder name ('order-service') and the package.json name field:

./services/order-service/package.json

{

"name": "your-name-here",

"version": "0.0.2",

"description": "An example Node.js app that is packed with best practices",

}

If you're just experimenting with Practica, you may leave the name as-is for now.

2. Add a new 'Edit' route

The express API routes are located in the entry-points layer, in the file 'routes.ts': [root]/services/order-service/entry-points/api/routes.ts

This is a very typical express code, if you're familiar with express you'll be productive right away. This is a core principle of Practica - it uses battle tested technologies as-is. Let's just add a new route in this file:

// A new route to edit order

router.put('/:id', async (req, res, next) => {

try {

logger.info(`Order API was called to edit order ${req.params.id}`);

// Later on we will call the main code in the domain layer

// Fow now let's put hard coded values

res.json({id:1, userId: 1, productId: 2, countryId: 1,

deliveryAddress: '123 Main St, New York',

paymentTermsInDays: 30}).status(200).end();

} catch (err) {

next(err);

}

});

✅Best practice: The API entry-point (controller) should stay thin and focus on forwarding the request to the domain layer.

Looks highly familiar, right? If not, it means you should learn first how to code first with your preferred framework - in this case it's Express. That's the thing with Practica - We don't replace neither abstract your reputable framework, we only augment it.

3. Test your first route

Commonly, once we have a first code skeleton, it's time to start testing it. In Practica we recommend writing 'component tests' against the API and including all the layers (no mocking), we have great examples for this under [root]/services/order-service/test

You may visit the file: [root]/services/order-service/test/add-order.test.ts, read one of the test and you're likely to get the intent shortly. Our testing guide will be released shortly.

🗝 Key insight: Practica's testing strategy is based on 'component tests' that include all the layers including the DB using docker-compose. We include rich testing patterns that mitigate various real-world risks like testing error handling, integrations and other things beyond the basics. Thanks to thoughtful setup, we're able to run 50 tests with DB in ~6 seconds. This is considered as a modern and highly-efficient strategy for testing Microservices

In this guide though, we're more focused on features craft - it's OK for now to test with POSTMAN or any other API explorer tool.

4. Create a DTO and a validation function

We're about to receive a payload from the caller, the edited order JSON. We obviously want to declare a strong schema/type so we can validate the incoming payloads and work with strong TypeScript types

✅Best practice: Validate incoming request and fail early. Both in run-time and development time

To meet these goals, we use two popular and powerful libraries: typebox and ajv. The first library, Typebox allows defining a schema with two outputs: TypeScript type and also JSON Schema. This is a standard and popular format that can be reused in many other places (e.g., to define OpenAPI spec). Based on this, the second library, ajv, will validate the requests.

Open the file [root]/services/order-service/domain/order-schema.ts

// Declare the basic order schema

import { Static, Type } from '@sinclair/typebox';

export const orderSchema = Type.Object({

deliveryAddress: Type.String(),

paymentTermsInDays: Type.Number(),

productId: Type.Integer(),

userId: Type.Integer(),

status: Type.Optional(Type.String()), // 👈 Add this field

});

This is Typebox's syntax for defines the basic order schema. Based on this we can get both JSON Schema and TypeScript type (!), this allows both run-time and development time protection. Add the status field to it and the following line to get a TypeScript type:

// This is a standard TypeScript type - we can use it now in the code and get intellisense + Typescript build-time validation

export type editOrderDTO = Static<typeof orderSchema>;

We have now strong development types to work with, it's time to configure our runtime validator. The library ajv gets JSON Schema, and validates the payload against it.

In the same file, let's define a validation function for edited orders:

// [root]/services/order-service/domain/order-schema

import { ajv } from '@practica/validation';

export function editOrderValidator() {

// For performance reason we cache the compiled validator function

const validator = ajv.getSchema<editOrderDTO>('edit-order');

if (!validator) {

ajv.addSchema(editOrderSchema, 'edit-order');

}

return ajv.getSchema<editOrderDTO>('edit-order')!;

}

We now have a TypeScript type and a function that can validate it on run-time. Knowing that we have safe types, it's time for the 'main thing' - coding the flow and logic

5. Create a use case (what the heck is 'use case'?)

Let's code our logic, but where? Obviously not in the controller/route which merely forwards request to our business logic layer. This should be done inside our domain folder, where the logic lives. Let's create a special type of code object - a use case.

A use-case is a plain JavaScript object/class which is created for every flow/feature. It summarizes the flow in a business and simple language without delving into the technical and small details. It mostly orchestrates other small services that hold all the implementation details. With use cases, the reader can grasp the high-level flow easily and avoid exposure to unnecessary complexity.

Let's add a new file inside the domain layer: edit-order-use-case.ts, and code the requirements:

// [root]/services/order-service/domain/edit-order-use-case.ts

import * as orderRepository from '../data-access/repositories/order-repository';

export default async function editOrder(orderId: number, updatedOrder: editOrderDTO) {

// Note how we use 👆 the editOrderDTO that was defined in the previous step

assertOrderIsValid(updatedOrder);

assertEditingIsAllowed(updatedOrder.status, updatedOrder.paymentTermsInDays);

// Call the DB layer here 👇 - to be explained soon

return await orderRepository.editOrder(orderId, updatedOrder);

}

Note how reading this function above easily tells the flow without messing with too much details. This is where use cases shine - by summarizing long details.

✅Best practice: Describe every feature/flow with a 'use case' object that summarizes the flow for better readability

Now we need to implement the functions that the use case calls. Since this is just a simple demo, we can put everything inside the use case. Consider a real-world scenario with heavier logic, calls to 3rd parties and DB work - In this case you'll need to spread this code across multiple services.

// [root]/services/order-service/domain/edit-order-use-case.ts

import { AppError } from '@practica/error-handling';

import { ajv } from '@practica/validation';

import { editOrderDTO, addOrderSchema } from './order-schema';

function assertOrderIsValid(updatedOrder: editOrderDTO) {

const isValid = ajv.validate(addOrderSchema, updatedOrder);

if (isValid === false) {

throw new AppError('invalid-order', `Validation failed`, 400, true);

}

}

function assertEditingIsAllowed( status: string | undefined,

paymentTermsInDays: number) {

if (status === 'delivered' || paymentTermsInDays === 0) {

throw new AppError(

'changes-not-allowed',

`It's not allow to delivered or paid orders`,

409, true);

}

}

🗝 Key insight: Note how everything we did thus far is mostly coding functions. No fancy constructs, no abstractions, not even classes - we try to keep things as simple as possible. You may of course use other language features when the need arises. We suggest by-default to stick to plain functions and use other constructs when a strong need is identified.

6. Put the data access code

We're tasked with saving the edited order in the database. Any DB-related code is located within the folder: [root]/services/order-service/data-access.

Practica supports two popular ORM, Sequelize (default) and Prisma. Whatever you chose, both are a battle-tested and reputable option that will surely serve you well as long as the DB complexity is not overwhelming.

Before discussing the ORM-side, we wrap the entire DB layer with a simple class that externalizes all the DB functions to the domain layer. This is the repository pattern which advocates decoupling the DB narratives from the one who codes business logic. Inside [root]/services/order-service/data-access/repositories, you'll find a file 'order-repository', open it and add a new function:

[root]/services/order-service/data-access/order-repository.js

import { getOrderModel } from './models/order-model';// 👈 This is the ORM code which will get explained soon

export async function editOrder(orderId: number, orderDetails): OrderRecord {

const orderEditingResponse = await getOrderModel().update(orderDetails, {

where: { id: orderId },

});

return orderEditingResponse;

}

Note that this file contains a type - OrderRecord. This is a plain JS object (POJO) that is used to interact with the data access layer. This approach prevents leaking DB/ORM narratives to the domain layer (e.g., ActiveRecord style)

✅Best practice: Externalize any DB data with a response that contains plain JavaScript objects (the repository pattern)

Add the new Status field to this type:

type OrderRecord = {

id: number;

// ... other existing fields

status: string;// 👈 Add this field per our requirements

};

Let's configure the ORM now and define the Order model - a mapper between JavaScript object and a database table (a common ORM notion). Open the file [root]/services/order-service/data-access/models/order-model.ts:

import { DataTypes } from 'sequelize';

import getDbConnection from '../db-connection';

export default function getOrderModel() {

// getDbConnection returns a singleton Sequelize (ORM) object - This is necessary to avoid multiple DB connection pools

return getDbConnection().define('Order', {

id: {

type: DataTypes.INTEGER,

primaryKey: true,

autoIncrement: true,

},

deliveryAddress: {

type: DataTypes.STRING,

},

//some other fields here

status: {

type: DataTypes.String,// 👈 Add this field per our requirements

allowNull: true

}

});

}

This file defines the mapping between our received and returned JavaScript object and the database. Given this definition, the ORM can now expose functions to interact with data.

7. 🥳 You have a robust working flow now

You should now be able to run the automated tests or POSTMAN and see the full flow working. It might feel like an overkill to create multiple layers and objects - naturally this level of modularization pays off when things get more complicated in real-world scenarios. Follow these layers and principles to write great code. In a short time, once you become familiar with these techniques - it will feel quick and natural

🗝 Key insight: Anything we went through in this article is not unique to Practica.js rather ubiquitous backend concepts. Practica.js brings no overhead beyond the common best practices. This knowledge will serve you in any other scenario, regardless of Practica.js

We will be grateful if you share with us how to make this guide better

- Ideas for future iterations: How to work with the Monorepo commands, Focus on a single componenent or run commands from the root, DB migration