Where the dead-bodies are covered

This post is about tests that are easy to write, 5-8 lines typically, they cover dark and dangerous corners of our applications, but are often overlooked

Some context first: How do we test a modern backend? With the testing diamond, of course, by putting the focus on component/integration tests that cover all the layers, including a real DB. With this approach, our tests 99% resemble the production and the user flows, while the development experience is almost as good as with unit tests. Sweet. If this topic is of interest, we've also written a guide with 50 best practices for integration tests in Node.js

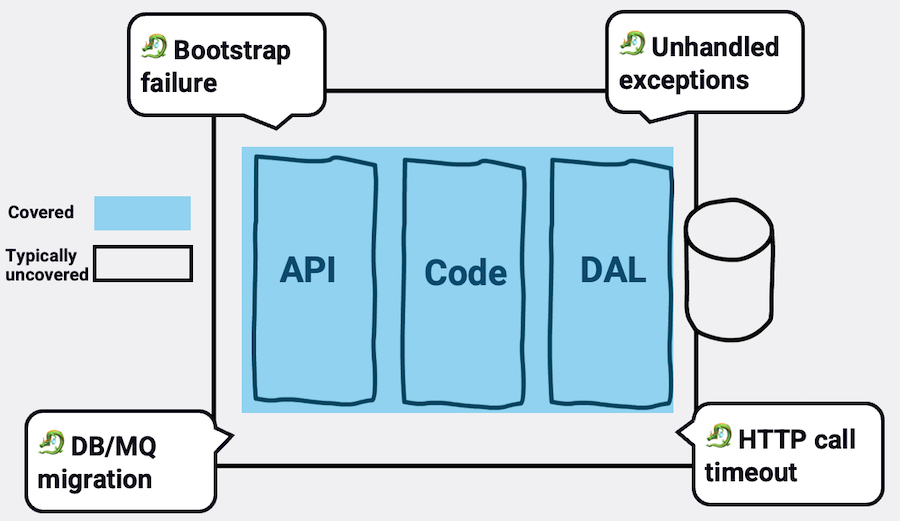

But there is a pitfall: most developers write only semi-happy test cases that are focused on the core user flows. Like invalid inputs, CRUD operations, various application states, etc. This is indeed the bread and butter, a great start, but a whole area is left uncovered. For example, typical tests don't simulate an unhandled promise rejection that leads to process crash, nor do they simulate the webserver bootstrap phase that might fail and leave the process idle, or HTTP calls to external services that often end with timeouts and retries. They typically not covering the health and readiness route, nor the integrity of the OpenAPI to the actual routes schema, to name just a few examples. There are many dead bodies covered beyond business logic, things that sometimes are even beyond bugs but rather are concerned with application downtime

Here are a handful of examples that might open your mind to a whole new class of risks and tests

July 2023: My testing course was launched: I've just released a comprehensive testing course that I've been working on for two years. 🎁 It's now on sale, but only for the month of July. Check it out at testjavascript.com

Test Examples

🧟♀️ The zombie process test

👉What & so what? - In all of your tests, you assume that the app has already started successfully, lacking a test against the initialization flow. This is a pity because this phase hides some potential catastrophic failures: First, initialization failures are frequent - many bad things can happen here, like a DB connection failure or a new version that crashes during deployment. For this reason, runtime platforms (like Kubernetes and others) encourage components to signal when they are ready (see readiness probe). Errors at this stage also have a dramatic effect over the app health - if the initialization fails and the process stays alive, it becomes a 'zombie process'. In this scenario, the runtime platform won't realize that something went bad, forward traffic to it and avoid creating alternative instances. Besides exiting gracefully, you may want to consider logging, firing a metric, and adjusting your /readiness route. Does it work? only test can tell!

📝 Code

Code under test, api.js:

// A common express server initialization

const startWebServer = () => {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

try {

// A typical Express setup

expressApp = express();

defineRoutes(expressApp); // a function that defines all routes

expressApp.listen(process.env.WEB_SERVER_PORT);

} catch (error) {

//log here, fire a metric, maybe even retry and finally:

process.exit();

}

});

};

The test:

const api = require('./entry-points/api'); // our api starter that exposes 'startWebServer' function

const sinon = require('sinon'); // a mocking library

test('When an error happens during the startup phase, then the process exits', async () => {

// Arrange

const processExitListener = sinon.stub(process, 'exit');

// 👇 Choose a function that is part of the initialization phase and make it fail

sinon

.stub(routes, 'defineRoutes')

.throws(new Error('Cant initialize connection'));

// Act

await api.startWebServer();

// Assert

expect(processExitListener.called).toBe(true);

});

👀 The observability test

👉What & why - For many, testing error means checking the exception type or the API response. This leaves one of the most essential parts uncovered - making the error correctly observable. In plain words, ensuring that it's being logged correctly and exposed to the monitoring system. It might sound like an internal thing, implementation testing, but actually, it goes directly to a user. Yes, not the end-user, but rather another important one - the ops user who is on-call. What are the expectations of this user? At the very basic level, when a production issue arises, she must see detailed log entries, including stack trace, cause and other properties. This info can save the day when dealing with production incidents. On to of this, in many systems, monitoring is managed separately to conclude about the overall system state using cumulative heuristics (e.g., an increase in the number of errors over the last 3 hours). To support this monitoring needs, the code also must fire error metrics. Even tests that do try to cover these needs take a naive approach by checking that the logger function was called - but hey, does it include the right data? Some write better tests that check the error type that was passed to the logger, good enough? No! The ops user doesn't care about the JavaScript class names but the JSON data that is sent out. The following test focuses on the specific properties that are being made observable:

📝 Code

test('When exception is throw during request, Then logger reports the mandatory fields', async () => {

//Arrange

const orderToAdd = {

userId: 1,

productId: 2,

status: 'approved',

};

const metricsExporterDouble = sinon.stub(metricsExporter, 'fireMetric');

sinon

.stub(OrderRepository.prototype, 'addOrder')

.rejects(new AppError('saving-failed', 'Order could not be saved', 500));

const loggerDouble = sinon.stub(logger, 'error');

//Act

await axiosAPIClient.post('/order', orderToAdd);

//Assert

expect(loggerDouble).toHaveBeenCalledWith({

name: 'saving-failed',

status: 500,

stack: expect.any(String),

message: expect.any(String),

});

expect(

metricsExporterDouble).toHaveBeenCalledWith('error', {

errorName: 'example-error',

})

});

👽 The 'unexpected visitor' test - when an uncaught exception meets our code

👉What & why - A typical error flow test falsely assumes two conditions: A valid error object was thrown, and it was caught. Neither is guaranteed, let's focus on the 2nd assumption: it's common for certain errors to left uncaught. The error might get thrown before your framework error handler is ready, some npm libraries can throw surprisingly from different stacks using timer functions, or you just forget to set someEventEmitter.on('error', ...). To name a few examples. These errors will find their way to the global process.on('uncaughtException') handler, hopefully if your code subscribed. How do you simulate this scenario in a test? naively you may locate a code area that is not wrapped with try-catch and stub it to throw during the test. But here's a catch22: if you are familiar with such area - you are likely to fix it and ensure its errors are caught. What do we do then? we can bring to our benefit the fact the JavaScript is 'borderless', if some object can emit an event, we as its subscribers can make it emit this event ourselves, here's an example:

researches says that, rejection

📝 Code

test('When an unhandled exception is thrown, then process stays alive and the error is logged', async () => {

//Arrange

const loggerDouble = sinon.stub(logger, 'error');

const processExitListener = sinon.stub(process, 'exit');

const errorToThrow = new Error('An error that wont be caught 😳');

//Act

process.emit('uncaughtException', errorToThrow); //👈 Where the magic is

// Assert

expect(processExitListener.called).toBe(false);

expect(loggerDouble).toHaveBeenCalledWith(errorToThrow);

});

🕵🏼 The 'hidden effect' test - when the code should not mutate at all

👉What & so what - In common scenarios, the code under test should stop early like when the incoming payload is invalid or a user doesn't have sufficient credits to perform an operation. In these cases, no DB records should be mutated. Most tests out there in the wild settle with testing the HTTP response only - got back HTTP 400? great, the validation/authorization probably work. Or does it? The test trusts the code too much, a valid response doesn't guarantee that the code behind behaved as design. Maybe a new record was added although the user has no permissions? Clearly you need to test this, but how would you test that a record was NOT added? There are two options here: If the DB is purged before/after every test, than just try to perform an invalid operation and check that the DB is empty afterward. If you're not cleaning the DB often (like me, but that's another discussion), the payload must contain some unique and queryable value that you can query later and hope to get no records. This is how it looks like:

📝 Code

it('When adding an invalid order, then it returns 400 and NOT retrievable', async () => {

//Arrange

const orderToAdd = {

userId: 1,

mode: 'draft',

externalIdentifier: uuid(), //no existing record has this value

};

//Act

const { status: addingHTTPStatus } = await axiosAPIClient.post(

'/order',

orderToAdd

);

//Assert

const { status: fetchingHTTPStatus } = await axiosAPIClient.get(

`/order/externalIdentifier/${orderToAdd.externalIdentifier}`

); // Trying to get the order that should have failed

expect({ addingHTTPStatus, fetchingHTTPStatus }).toMatchObject({

addingHTTPStatus: 400,

fetchingHTTPStatus: 404,

});

// 👆 Check that no such record exists

});

🧨 The 'overdoing' test - when the code should mutate but it's doing too much

👉What & why - This is how a typical data-oriented test looks like: first you add some records, then approach the code under test, and finally assert what happens to these specific records. So far, so good. There is one caveat here though: since the test narrows it focus to specific records, it ignores whether other record were unnecessarily affected. This can be really bad, here's a short real-life story that happened to my customer: Some data access code changed and incorporated a bug that updates ALL the system users instead of just one. All test pass since they focused on a specific record which positively updated, they just ignored the others. How would you test and prevent? here is a nice trick that I was taught by my friend Gil Tayar: in the first phase of the test, besides the main records, add one or more 'control' records that should not get mutated during the test. Then, run the code under test, and besides the main assertion, check also that the control records were not affected:

📝 Code

test('When deleting an existing order, Then it should NOT be retrievable', async () => {

// Arrange

const orderToDelete = {

userId: 1,

productId: 2,

};

const deletedOrder = (await axiosAPIClient.post('/order', orderToDelete)).data

.id; // We will delete this soon

const orderNotToBeDeleted = orderToDelete;

const notDeletedOrder = (

await axiosAPIClient.post('/order', orderNotToBeDeleted)

).data.id; // We will not delete this

// Act

await axiosAPIClient.delete(`/order/${deletedOrder}`);

// Assert

const { status: getDeletedOrderStatus } = await axiosAPIClient.get(

`/order/${deletedOrder}`

);

const { status: getNotDeletedOrderStatus } = await axiosAPIClient.get(

`/order/${notDeletedOrder}`

);

expect(getNotDeletedOrderStatus).toBe(200);

expect(getDeletedOrderStatus).toBe(404);

});

🕰 The 'slow collaborator' test - when the other HTTP service times out

👉What & why - When your code approaches other services/microservices via HTTP, savvy testers minimize end-to-end tests because these tests lean toward happy paths (it's harder to simulate scenarios). This mandates using some mocking tool to act like the remote service, for example, using tools like nock or wiremock. These tools are great, only some are using them naively and check mainly that calls outside were indeed made. What if the other service is not available in production, what if it is slower and times out occasionally (one of the biggest risks of Microservices)? While you can't wholly save this transaction, your code should do the best given the situation and retry, or at least log and return the right status to the caller. All the network mocking tools allow simulating delays, timeouts and other 'chaotic' scenarios. Question left is how to simulate slow response without having slow tests? You may use fake timers and trick the system into believing as few seconds passed in a single tick. If you're using nock, it offers an interesting feature to simulate timeouts quickly: the .delay function simulates slow responses, then nock will realize immediately if the delay is higher than the HTTP client timeout and throw a timeout event immediately without waiting

📝 Code

// In this example, our code accepts new Orders and while processing them approaches the Users Microservice

test('When users service times out, then return 503 (option 1 with fake timers)', async () => {

//Arrange

const clock = sinon.useFakeTimers();

config.HTTPCallTimeout = 1000; // Set a timeout for outgoing HTTP calls

nock(`${config.userServiceURL}/user/`)

.get('/1', () => clock.tick(2000)) // Reply delay is bigger than configured timeout 👆

.reply(200);

const loggerDouble = sinon.stub(logger, 'error');

const orderToAdd = {

userId: 1,

productId: 2,

mode: 'approved',

};

//Act

// 👇try to add new order which should fail due to User service not available

const response = await axiosAPIClient.post('/order', orderToAdd);

//Assert

// 👇At least our code does its best given this situation

expect(response.status).toBe(503);

expect(loggerDouble.lastCall.firstArg).toMatchObject({

name: 'user-service-not-available',

stack: expect.any(String),

message: expect.any(String),

});

});

💊 The 'poisoned message' test - when the message consumer gets an invalid payload that might put it in stagnation

👉What & so what - When testing flows that start or end in a queue, I bet you're going to bypass the message queue layer, where the code and libraries consume a queue, and you approach the logic layer directly. Yes, it makes things easier but leaves a class of uncovered risks. For example, what if the logic part throws an error or the message schema is invalid but the message queue consumer fails to translate this exception into a proper message queue action? For example, the consumer code might fail to reject the message or increment the number of attempts (depends on the type of queue that you're using). When this happens, the message will enter a loop where it always served again and again. Since this will apply to many messages, things can get really bad as the queue gets highly saturated. For this reason this syndrome was called the 'poisoned message'. To mitigate this risk, the tests' scope must include all the layers like how you probably do when testing against APIs. Unfortunately, this is not as easy as testing with DB because message queues are flaky, here is why

When testing with real queues things get curios and curiouser: tests from different process will steal messages from each other, purging queues is harder that you might think (e.g. SQS demand 60 seconds to purge queues), to name a few challenges that you won't find when dealing with real DB

Here is a strategy that works for many teams and holds a small compromise - use a fake in-memory message queue. By 'fake' I mean something simplistic that acts like a stub/spy and do nothing but telling when certain calls are made (e.g., consume, delete, publish). You might find reputable fakes/stubs for your own message queue like this one for SQS and you can code one easily yourself. No worries, I'm not a favour of maintaining myself testing infrastructure, this proposed component is extremely simply and unlikely to surpass 50 lines of code (see example below). On top of this, whether using a real or fake queue, one more thing is needed: create a convenient interface that tells to the test when certain things happened like when a message was acknowledged/deleted or a new message was published. Without this, the test never knows when certain events happened and lean toward quirky techniques like polling. Having this setup, the test will be short, flat and you can easily simulate common message queue scenarios like out of order messages, batch reject, duplicated messages and in our example - the poisoned message scenario (using RabbitMQ):

📝 Code

- Create a fake message queue that does almost nothing but record calls, see full example here

class FakeMessageQueueProvider extends EventEmitter {

// Implement here

publish(message) {}

consume(queueName, callback) {}

}

- Make your message queue client accept real or fake provider

class MessageQueueClient extends EventEmitter {

// Pass to it a fake or real message queue

constructor(customMessageQueueProvider) {}

publish(message) {}

consume(queueName, callback) {}

// Simple implementation can be found here:

// https://github.com/testjavascript/nodejs-integration-tests-best-practices/blob/master/example-application/libraries/fake-message-queue-provider.js

}

- Expose a convenient function that tells when certain calls where made

class MessageQueueClient extends EventEmitter {

publish(message) {}

consume(queueName, callback) {}

// 👇

waitForEvent(eventName: 'publish' | 'consume' | 'acknowledge' | 'reject', howManyTimes: number) : Promise

}

- The test is now short, flat and expressive 👇

const FakeMessageQueueProvider = require('./libs/fake-message-queue-provider');

const MessageQueueClient = require('./libs/message-queue-client');

const newOrderService = require('./domain/newOrderService');

test('When a poisoned message arrives, then it is being rejected back', async () => {

// Arrange

const messageWithInvalidSchema = { nonExistingProperty: 'invalid❌' };

const messageQueueClient = new MessageQueueClient(

new FakeMessageQueueProvider()

);

// Subscribe to new messages and passing the handler function

messageQueueClient.consume('orders.new', newOrderService.addOrder);

// Act

await messageQueueClient.publish('orders.new', messageWithInvalidSchema);

// Now all the layers of the app will get stretched 👆, including logic and message queue libraries

// Assert

await messageQueueClient.waitFor('reject', { howManyTimes: 1 });

// 👆 This tells us that eventually our code asked the message queue client to reject this poisoned message

});

📝Full code example - is here

📦 Test the package as a consumer

👉What & why - When publishing a library to npm, easily all your tests might pass BUT... the same functionality will fail over the end-user's computer. How come? tests are executed against the local developer files, but the end-user is only exposed to artifacts that were built. See the mismatch here? after running the tests, the package files are transpiled (I'm looking at you babel users), zipped and packed. If a single file is excluded due to .npmignore or a polyfill is not added correctly, the published code will lack mandatory files

📝 Code

Consider the following scenario, you're developing a library, and you wrote this code:

// index.js

export * from './calculate.js';

// calculate.js 👈

export function calculate() {

return 1;

}

Then some tests:

import { calculate } from './index.js';

test('should return 1', () => {

expect(calculate()).toBe(1);

})

✅ All tests pass 🎊

Finally configure the package.json:

{

// ....

"files": [

"index.js"

]

}

See, 100% coverage, all tests pass locally and in the CI ✅, it just won't work in production 👹. Why? because you forgot to include the calculate.js in the package.json files array 👆

What can we do instead? we can test the library as its end-users. How? publish the package to a local registry like verdaccio, let the tests install and approach the published code. Sounds troublesome? judge yourself 👇

📝 Code

// global-setup.js

// 1. Setup the in-memory NPM registry, one function that's it! 🔥

await setupVerdaccio();

// 2. Building our package

await exec('npm', ['run', 'build'], {

cwd: packagePath,

});

// 3. Publish it to the in-memory registry

await exec('npm', ['publish', '--registry=http://localhost:4873'], {

cwd: packagePath,

});

// 4. Installing it in the consumer directory

await exec('npm', ['install', 'my-package', '--registry=http://localhost:4873'], {

cwd: consumerPath,

});

// Test file in the consumerPath

// 5. Test the package 🚀

test("should succeed", async () => {

const { fn1 } = await import('my-package');

expect(fn1()).toEqual(1);

});

📝Full code example - is here

What else this technique can be useful for?

- Testing different version of peer dependency you support - let's say your package support react 16 to 18, you can now test that

- You want to test ESM and CJS consumers

- If you have CLI application you can test it like your users

- Making sure all the voodoo magic in that babel file is working as expected

🗞 The 'broken contract' test - when the code is great but its corresponding OpenAPI docs leads to a production bug

👉What & so what - Quite confidently I'm sure that almost no team test their OpenAPI correctness. "It's just documentation", "we generate it automatically based on code" are typical belief found for this reason. Let me show you how this auto generated documentation can be wrong and lead not only to frustration but also to a bug. In production.

Consider the following scenario, you're requested to return HTTP error status code if an order is duplicated but forget to update the OpenAPI specification with this new HTTP status response. While some framework can update the docs with new fields, none can realize which errors your code throws, this labour is always manual. On the other side of the line, the API client is doing everything just right, going by the spec that you published, adding orders with some duplication because the docs don't forbid doing so. Then, BOOM, production bug -> the client crashes and shows an ugly unknown error message to the user. This type of failure is called the 'contract' problem when two parties interact, each has a code that works perfect, they just operate under different spec and assumptions. While there are fancy sophisticated and exhaustive solution to this challenge (e.g., PACT), there are also leaner approaches that gets you covered easily and quickly (at the price of covering less risks).

The following sweet technique is based on libraries (jest, mocha) that listen to all network responses, compare the payload against the OpenAPI document, and if any deviation is found - make the test fail with a descriptive error. With this new weapon in your toolbox and almost zero effort, another risk is ticked. It's a pity that these libs can't assert also against the incoming requests to tell you that your tests use the API wrong. One small caveat and an elegant solution: These libraries dictate putting an assertion statement in every test - expect(response).toSatisfyApiSpec(), a bit tedious and relies on human discipline. You can do better if your HTTP client supports plugin/hook/interceptor by putting this assertion in a single place that will apply in all the tests:

📝 Code

Code under test, an API throw a new error status

if (doesOrderCouponAlreadyExist) {

throw new AppError('duplicated-coupon', { httpStatus: 409 });

}

The OpenAPI doesn't document HTTP status '409', no framework knows to update the OpenAPI doc based on thrown exceptions

"responses": {

"200": {

"description": "successful",

}

,

"400": {

"description": "Invalid ID",

"content": {}

},// No 409 in this list😲👈

}

The test code

const jestOpenAPI = require('jest-openapi');

jestOpenAPI('../openapi.json');

test('When an order with duplicated coupon is added , then 409 error should get returned', async () => {

// Arrange

const orderToAdd = {

userId: 1,

productId: 2,

couponId: uuid(),

};

await axiosAPIClient.post('/order', orderToAdd);

// Act

// We're adding the same coupon twice 👇

const receivedResponse = await axios.post('/order', orderToAdd);

// Assert;

expect(receivedResponse.status).toBe(409);

expect(res).toSatisfyApiSpec();

// This 👆 will throw if the API response, body or status, is different that was it stated in the OpenAPI

});

Trick: If your HTTP client supports any kind of plugin/hook/interceptor, put the following code in 'beforeAll'. This covers all the tests against OpenAPI mismatches

beforeAll(() => {

axios.interceptors.response.use((response) => {

expect(response.toSatisfyApiSpec());

// With this 👆, add nothing to the tests - each will fail if the response deviates from the docs

});

});

Even more ideas

- Test readiness and health routes

- Test message queue connection failures

- Test JWT and JWKS failures

- Test security-related things like CSRF tokens

- Test your HTTP client retry mechanism (very easy with nock)

- Test that the DB migration succeed and the new code can work with old records format

- Test DB connection disconnects

It's not just ideas, it a whole new mindset

The examples above were not meant only to be a checklist of 'don't forget' test cases, but rather a fresh mindset on what tests could cover for you. Modern tests are not just about functions, or user flows, but any risk that might visit your production. This is doable only with component/integration tests but never with unit or end-to-end tests. Why? Because unlike unit you need all the parts to play together (e.g., the DB migration file, with the DAL layer and the error handler all together). Unlike E2E, you have the power to simulate in-process scenarios that demand some tweaking and mocking. Component tests allow you to include many production moving parts early on your machine. I like calling this 'production-oriented development'

My new online testing course - If you're intrigued with beyond the basics testing patterns, consider my online course which was just launched and is 🎁 on sale for 30 days (July 2023)